Historic

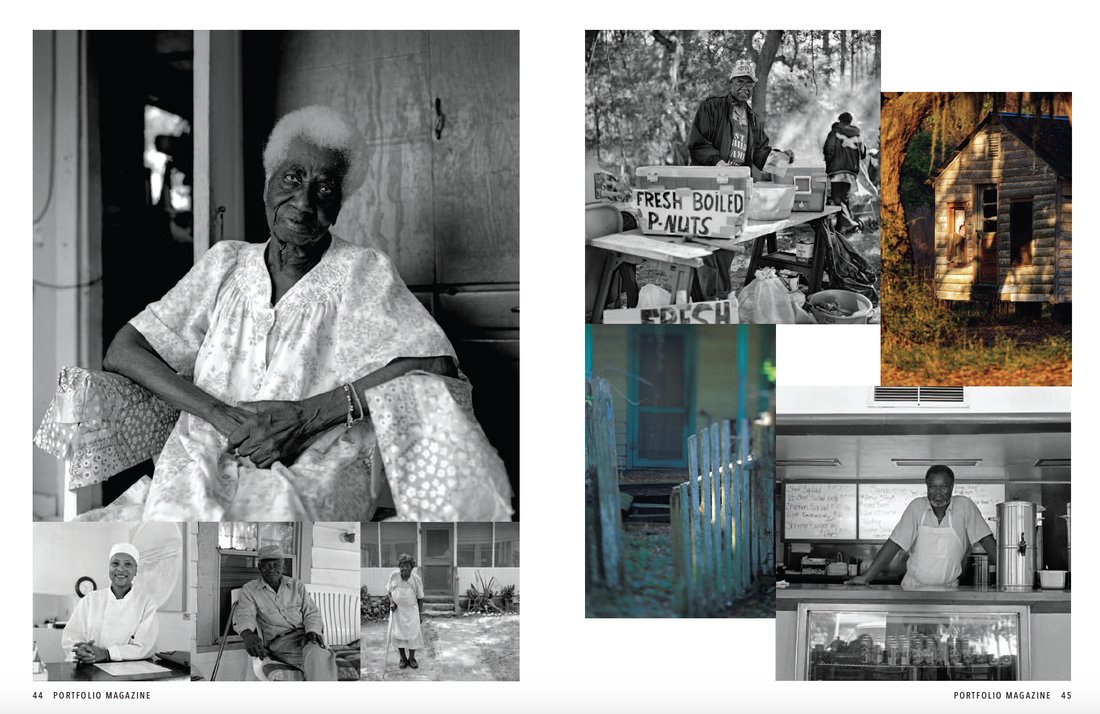

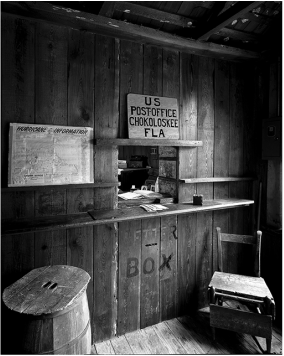

HISTORIC SMALLWOOD STOREChokoloskee Island, Florida.

Est. 1906 by Ted Smallwood. Photography: John Gillan Portrait, Nancy Smallwood

|

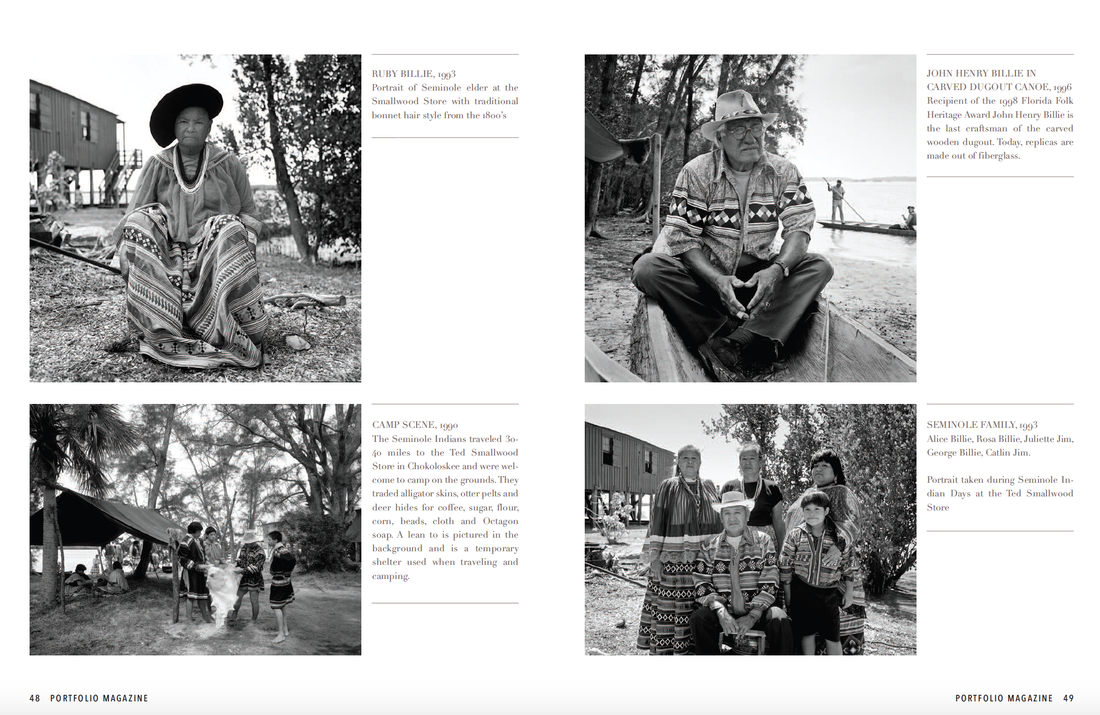

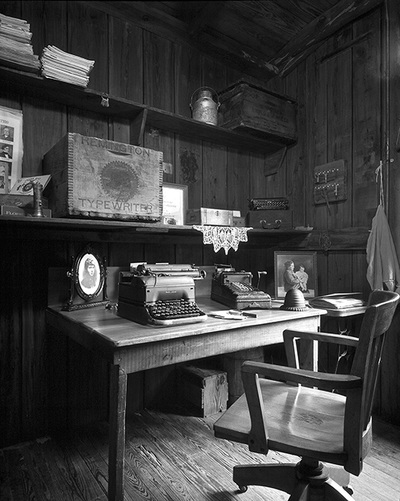

Ted Smallwood Store Old Indian Trading Post, 1990

The Ted Smallwood Store is located in southwest Florida on the island of Chokoloskee in the 10,000 islands. Until 1955, the island was only accessible by boat and was populated mainly by fisherman and hunters. Smallwood’s Store was the market for their catches as well as their source for supplies. The store served as a post office, general store, drug store, fuel store and hardware store, as well as a social gathering place and a Seminole Indian trading post. Chokoloskee was originally a shell mound built and inhabited by prehistoric Indians. The seawall was tabby, constructed of shell, cement and sand. The timbers that support the store are made of Southern Yellow Pine. The building was raised on pilings after a flood in 1924. |

Gillan's early interest in photography was cemented by the opportunity to photograph President John F. Kennedy who was presenting his father with the Bronze star. Two days later, Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas and Gillan realized the importance of photography as a means of capturing and communicating history.

As a photojournalist in the United States Air Force during the end of the Vietnam War era, Gillan refined his vision and began mastering his range of photographic techniques. These ranged from the classic studio 8x10 portrait to photographing dignitaries on location such as Nixon, Carter and Queen Elizabeth of England.

Internationally recognized for his body of work, John Gillan pairs his vision with a wide range of contemporary and primitive photographic techniques to create compelling images. 1994, Gillan was a guest lecturer at the 25th Annual International Photography Encounter in Arles, France where he taught platinum printing and Polaroid transfer at the request of his mentor, famed French photographer, Lucien Clergue.

For the past two decades, Gillan's work has been exhibited in galleries and museums internationally and is part of many private collections. It has been featured in diverse publications including Architectural Record, Architectural Digest, Historic Preservation and Florida Architecture. In 1998, was awarded Best of Show Award from the Advertising Federation of America and the 1996 and in 2005 was named the Architectural Photographer of the Year Award from the American Institute of Architects.

His publications include “100 - Life at 100 and Beyond”, Places in Time – Historic Architecture and Landscape of Miami and Miami Melange featuring a portion of the 100 pieces of his work in the Hunton & Williams collection.

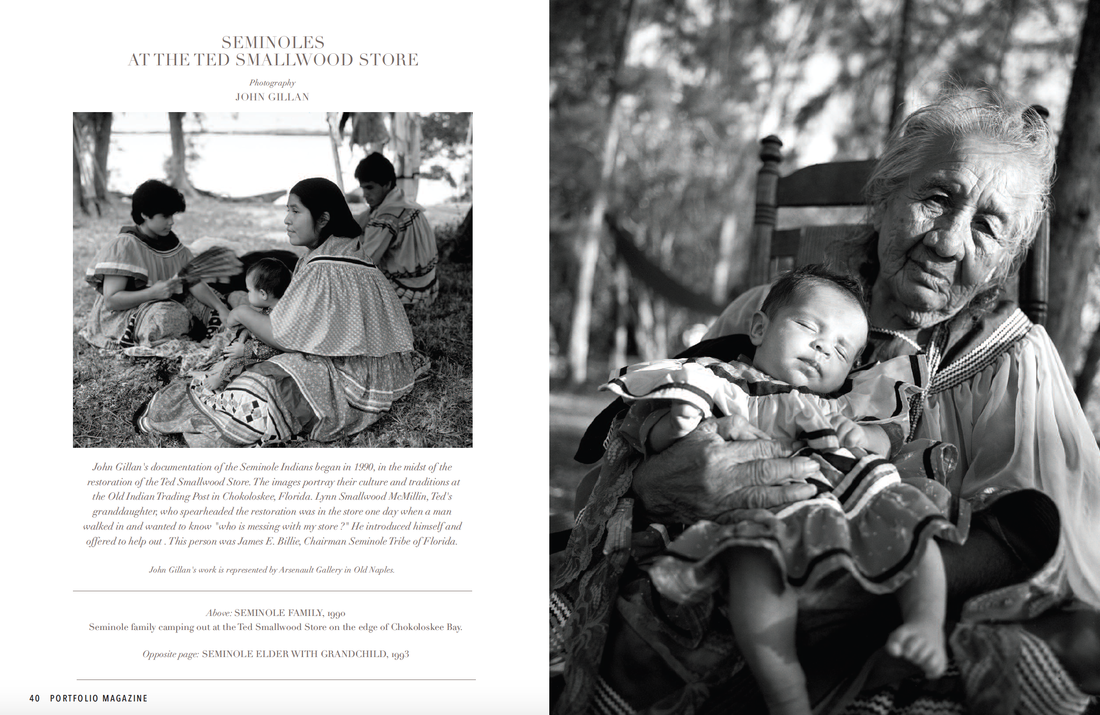

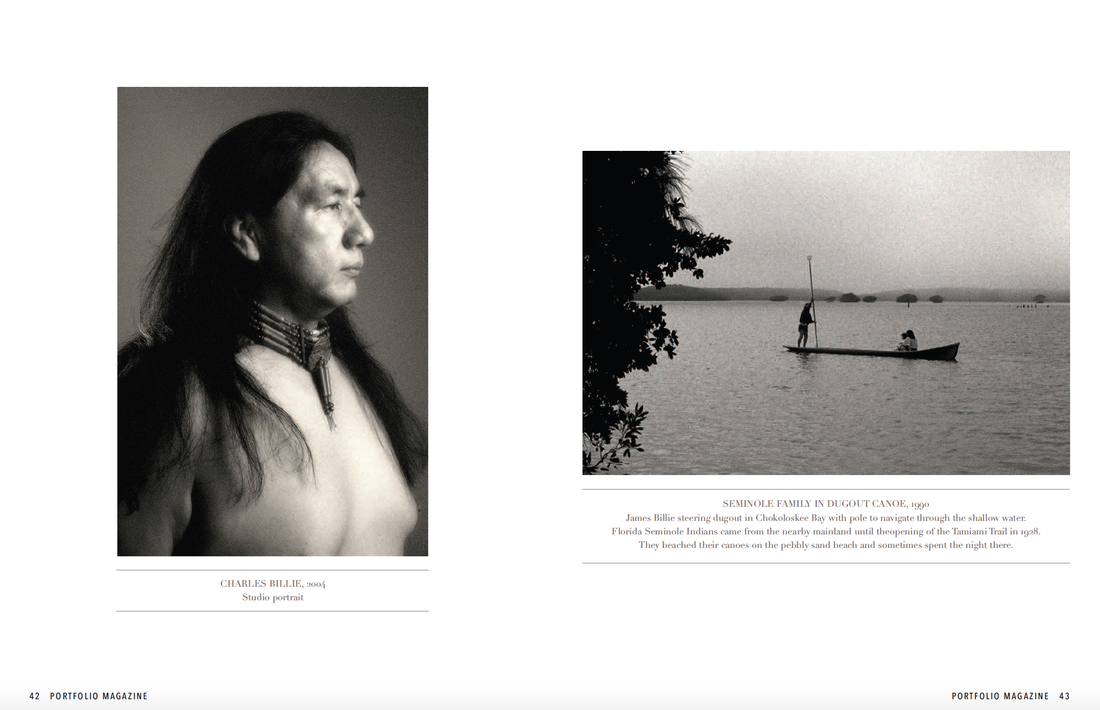

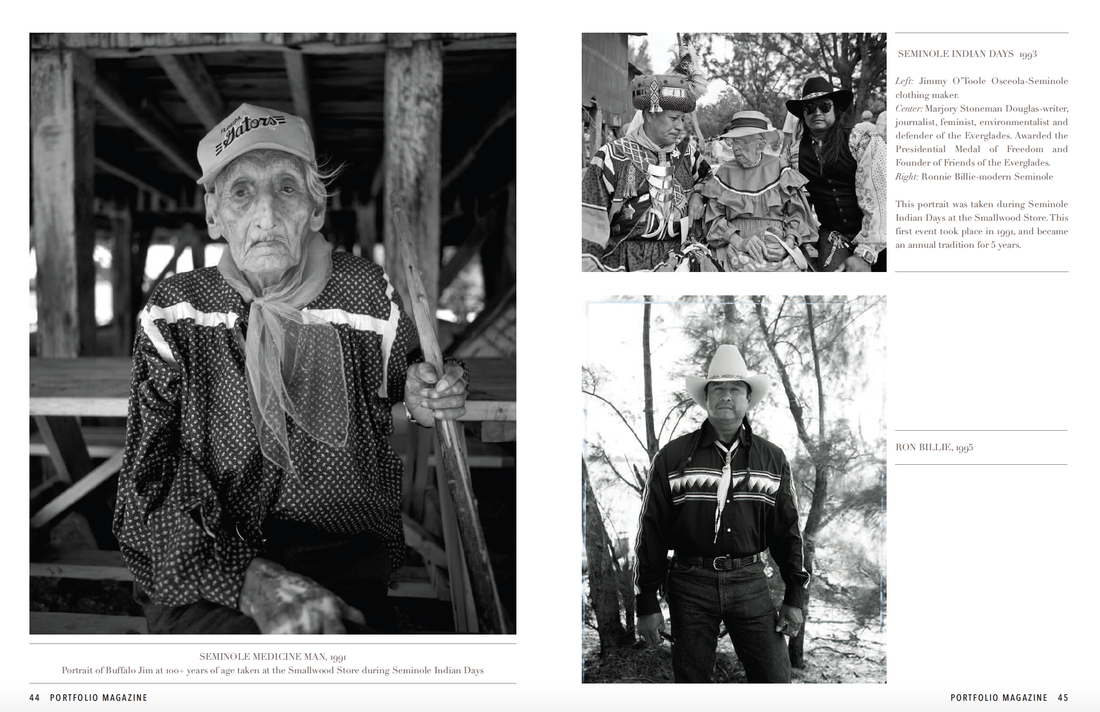

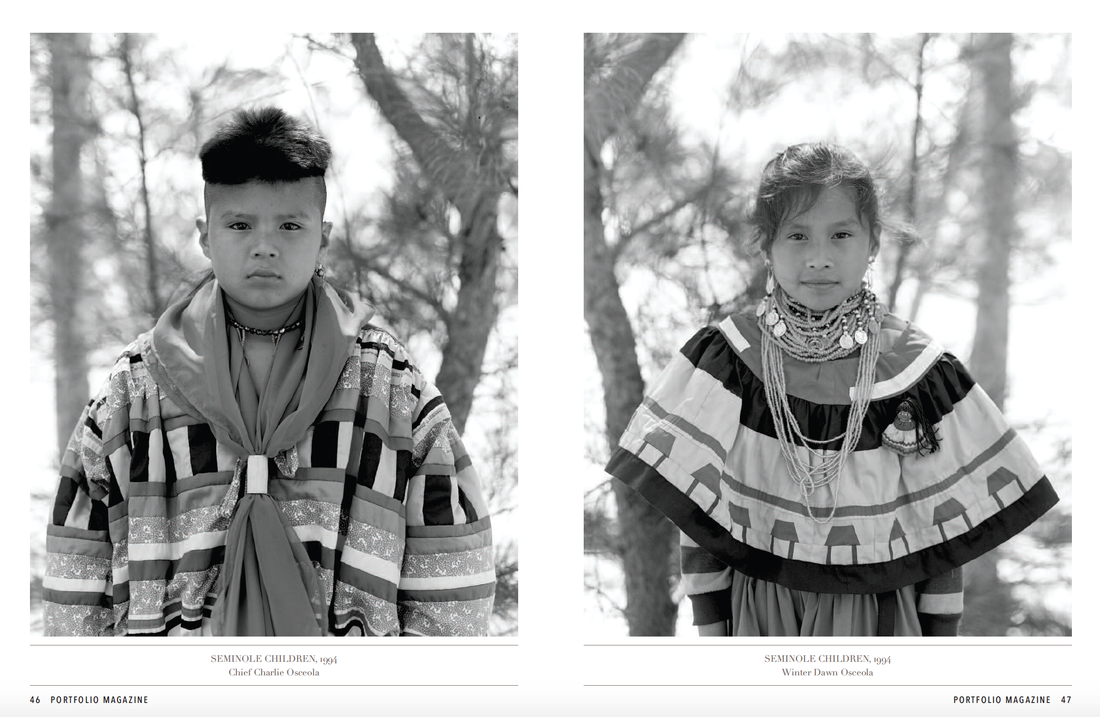

John embarked on a two year photographic documentation of the Smallwood Store after being enchantered by this rare piece of forgotten Florida history and the desire to help preserve the store for generations to come. On this journey he was introduced to the Seminoles and the body of work expanded to includ them. This documentation lasted many years.

A Polacolor Emulsion Transfer exhibit of the Ted Smallwood Store travelled the state of Florida with funding from a grant awarded by the Florida Humanities Council in 1989. Arsenault Studio & Banyan Arts Gallery is proud to feature Gillan's photography.

His publications include “100 - Life at 100 and Beyond”, Places in Time – Historic Architecture and Landscape of Miami and Miami Melange featuring a portion of the 100 pieces of his work in the Hunton & Williams collection.

John embarked on a two year photographic documentation of the Smallwood Store after being enchantered by this rare piece of forgotten Florida history and the desire to help preserve the store for generations to come. On this journey he was introduced to the Seminoles and the body of work expanded to includ them. This documentation lasted many years.

A Polacolor Emulsion Transfer exhibit of the Ted Smallwood Store travelled the state of Florida with funding from a grant awarded by the Florida Humanities Council in 1989. Arsenault Studio & Banyan Arts Gallery is proud to feature Gillan's photography.

ENCHANTMENTS

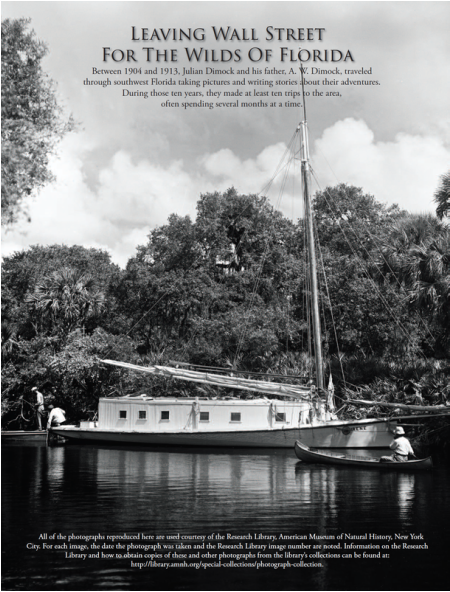

Julian Dimock’s Photographs of Southwest Florida

Between 1904 and 1913, Julian Dimock and his father, A. W. Dimock, traveled through southwest Florida taking pictures and writing stories about their adventures. During those ten years, they made at least ten trips to the area, often spending several months at a time.

|

New York financiers who had been discredited by A. W.’s legal and financial problems, the Dimocks had left Wall Street for the wilds of Florida. Using Marco Island as their base, they motored and sailed the Gulf littoral in their houseboat, the Irene, on which they carried or towed a skiff, canoe, and small powerboat. Using the smaller craft, they traversed many of the rivers flowing into the Ten Thousand Islands. On occasion, they canoed well into the Everglades and the Big Cypress Swamp, twice going all the way to Miami. Julian and A. W. also traveled overland via oxcart and mule-drawn wagon to reach places like Deep Lake Plantation on the mainland. They frequently camped out, sometimes for days or weeks at a time. On all of these adventures, Julian used his cameras to take photographs.

When they were done, Julian Dimock had amassed nearly two thousand photographs of Florida, all on glass negatives. His photographs illustrated nearly eighty magazine and newspaper articles on Florida written by him and/or his father for Collier’s, Field and Stream, Harper’s, Scribner’s, and other periodicals (a listing can be found at the end of this book). Some of the articles were reprinted in A. W.’s 1908 book Florida Enchantments (an expanded and revised edition was issued in 1915). A. W. also authored several books for young adults, including Dick in the Everglades (1909) and Be Prepared, or the Boy Scouts in Florida (1912). All of the books featured Julian’s photographs. Julian also supplied photographs to magazines to illustrate articles written by others. |

By the time A. W. died in 1918 at age seventy-six, Julian had married and moved to Vermont, where he had taken up farming (Julian died at seventy-three in 1945). In 1920, Julian gave his collection of exposed-glass plates to the American Museum of Natural History. Julian’s photographs, especially when viewed in the context of the articles and books written by him and his father, provide an extraordinary record of southwest Florida in the early 1900s.

Southwest Florida in the First Decade of the Twentieth Century

Twentieth century? The words sound very modern. But in the spring of 1904, when A. W. and Julian Dimock traveled to Marco Island and began to amass their trove of photographs, the island lay on the southern edge of the United States’ frontier. Following the Civil War, the frontier had crept down the Gulf coast until it hit the Ten Thousand Islands, an untamed, verdant labyrinth of mangroves, shell mounds, small islands, and innumerable streams. Settlements on Marco Island, at Henderson Creek just to the north on the mainland east of Rookery Bay, and at Everglades City (then known only as Everglade) to the south on Chokoloskee Bay marked the boundary between Anglo “civilization” to the north and the Ten Thousand Islands and the wetlands of the Big Cypress Swamp and the Everglades to the east. Farming and settling lands along the Caloosahatchee River, where Fort Myers was located, or on Marco Island was one thing; wresting a living from the Ten Thousand Islands was another.

In one sense, the Ten Thousand Islands were a barrier to further expansion down the Gulf coast. But they also were an “in-between,” a region whose unique physiography separated Marco Island and the other islands and the mainland in and around Charlotte Harbor and Pine Island Sound in the north from the vast wetlands of the Big Cypress Swamp and the Everglades to the south and east. Those wetlands spread across south Florida from the Gulf coast to Miami and the nascent settlements on Florida’s lower Atlantic coast. Far to the south, at the tip of the Florida Keys, lay the “metropolis” of Key West, south Florida’s largest town. Key West’s founding had leapfrogged the relatively unfriendly (to Anglos) Ten Thousand Islands and the wetlands of interior south Florida.

In a cultural sense, too, the Ten Thousand Islands were an “in-between.” Anglos were living from Marco Island north along the Gulf coast, localities they had settled in the mid-nineteenth century or earlier, while the Big Cypress and the Everglades were home to Seminole Indians whose ancestors first had made their homes there in the nineteenth century. The Ten Thousand Islands themselves were sparsely populated.

A glance at the U.S. census from 1900 supports the contention that the frontier reached down the Gulf coast only to southwest Florida at the time the Dimocks were there. In that year, all of south Florida below Lake Okeechobee—then comprised of only three counties: Dade, Lee, and Monroe—had a total population of 26,000 people, of whom 18,000 were in Key West (Monroe County), 4,955 in Dade County, and 3,071 in Lee County, including fewer than 1,000 in Fort Myers. At the same time, Florida’s total population was 528,000, while New York City held a whopping 3.44 million residents.

In 1900, southwest Florida was the sticks and Fort Myers was a frontier town, though its citizens probably would have contested that characterization. The Dimocks, on the other hand, would have agreed. In “A Summer Florida Vacation,” a magazine article he published in July 1905, Julian wrote that though he loved Marco, if one wanted a newspaper, one had to go all the way to Sarasota, a town with regular railroad connections and other “superfluities of the modern day.” Fort Myers apparently did not enter into his thinking as an outpost of civilization.

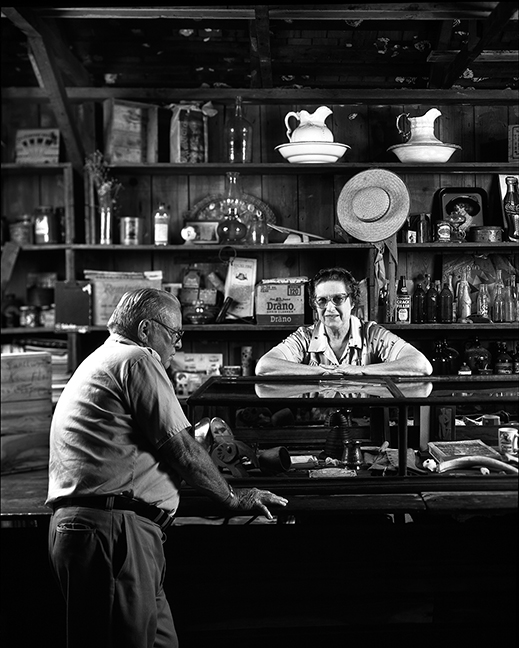

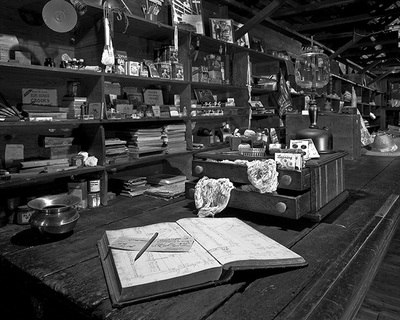

The Dimocks would discover that the Ten Thousand Islands, the “in-between,” served as a common ground where Anglos and Seminole Indians came in contact with one another. At places like Storter’s trading post and store in Everglades City at the north end of the Ten Thousand Islands, white settlers and tourists came face to face with Seminole Indians who brought hides, feathers, and other goods to sell and trade for the items they wanted. Otter pelts, buckskin, and alligator hides moved west; cloth, guns, ammunition, pails, ceramic jugs, and tobacco went back east; photographs of Seminoles Indians went back north.

Photographing Southwest Florida

It was at Storter’s store in April 1905 that Julian Dimock and his father first met and photographed Seminole Indians. That initial meeting would lead to the Dimocks making forays into the Big Cypress and Everglades to document the Seminole people in their traditional camps. Sometimes they were guided, not always successfully, by local residents of Everglades City. Other times they employed Seminole Indian guides to lead them and introduce them to the native inhabitants of the Big Cypress and Everglades, people still smarting from the horrific attempts by the U.S. government and its armies to forcibly resettle them in Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River.

The Seminole Indians had not forgotten the wars of the 1830s and early 1840s and the mid-1850s, when federal and state troops had invaded interior south Florida. Understandably, the Seminoles remained extremely suspicious of white people like the Dimocks who traveled there, thinking they might be federal agents. It is a tribute to both the Seminoles and to Julian and A. W. that the latter were allowed to travel reasonably freely to Seminole camps and take photographs. As a consequence, Julian’s photographs of Seminole Indians provide an unparalleled visual record of the Seminole people just prior to the time when the United States’ frontier moved into southern Florida, bringing with it efforts to drain, ditch, and dike large portions of the area, altering the centuries-old water regime. A selection of those Seminole Indian photographs, each with Julian’s information about the individuals depicted and the date and place each photograph was taken, can be found in our book Hidden Seminoles: Julian Dimock’s Historic Florida Photographs (2011).

Julian not only used his camera to document the Seminole Indians; he also photographed white and African American people and their activities on Marco Island and at Henderson Creek and Deep Lake Plantation on the mainland. In the Ten Thousand Islands, he spent considerable effort photographing rookeries of the birds then being threatened by plume hunters. Several of his illustrated articles decried the slaughter of thousands of birds to satisfy the demands of haute couture in New York and Europe.

Julian also sought to record information about other southwest Florida animals, including manatees, alligators, and crocodiles. Mangroves and other plants caught his camera’s eye as well. The most photographed resident of southwest Florida, however, one that Julian and his father spent literally months taking pictures of, was Megalops atlanticus, the Atlantic tarpon. To photograph a tarpon, one first had to catch the animal—not an easy task—and then wait for him to jump. Julian and his father both became expert tarpon fishermen, and Julian became an even more expert tarpon photographer, taking hundreds of shots of leaping tarpon and even writing magazine articles on how best to capture a tarpon in midleap. His father went one better. In 1911, he published The Book of the Tarpon (illustrated by Julian), which, a century later, is still in print and a favorite of anglers.

Julian was a gifted photographer whose father dubbed him “the camera-man.” A. W., whose skill was writing, called himself “the scribe.” His magazine articles and Julian’s photographs together are an enchantment, a fascinating record of a time and place that still delights us today.

Southwest Florida Travels

When Julian and A. W. Dimock traveled to southwest Florida, they apparently spent little or no time in Fort Myers, which was simply their jumping-off place for Marco Island and southwest Florida. To reach Fort Myers from their homes in New York, Julian and his father took a train or steamship to Jacksonville, then a train to Fort Myers. At Punta Rassa at the mouth of the Caloosahatchee River west of Fort Myers, they bought a ride on the mail boat that took them and their supplies—including Julian’s cameras, tripod, boxes of glass plates, and chemicals needed for processing the plates—to Marco Island 40 miles south. The total cost of the round trip from New York to Marco and return was $71 (New York to Jacksonville and back, $50; train to Fort Myers and back to Jacksonville, $16; round-trip mail boat to Marco, $5). Still another alternative was to travel from New York to Key West by sea and then take a smaller boat to Marco Island, but the Dimocks clearly did not relish that itinerary, noting that the boats from Key West to Marco were home to hordes of cockroaches. They also preferred taking a steamship to Jacksonville because the trains from New York were uncomfortable and often hot. Either way, the transition from life in New York City to the Florida frontier must have been jarring at best.

On Marco Island, the Dimocks likely stayed at the twenty-room Marco Hotel, owned by William D. “Bill” Collier, that was located in the small settlement on the northern end of the island (known today as Old Marco Village). The Dimocks, however, nowhere provide information about their accommodations or what the village was like, and Julian did not take a single photograph in the village.

Julian’s earliest photographs of southwest Florida are from late May 1904. That summer, he and his father apparently stayed on the island for two and a half months before returning north, a pattern that modern snowbirds, who prefer winters in Florida, might find perverse. During that time, they traveled around Marco Island and its nearby waters, probably in rented boats or with local residents, exploring, learning, and photographing. Returning to Marco in November and staying into February 1905, they traveled to the mainland, first to the small Henderson Creek settlement and then to Deep Lake Plantation in the Big Cypress Swamp. Julian, perhaps with his father, also traveled north to the St. Johns River Valley to photograph orange groves. Julian may have been on assignment for Country Calendar magazine, whose first issue would be published in 1905. It was about this time, late 1904, that the Dimocks decided to buy a boat so they could travel farther afield on their own.

The Irene, as they named their 37-foot houseboat, was well suited to the shallow waters of the coast. After hiring a captain who knew the local waters and one or two crew members (the latter called “boys” by the Dimocks), Julian and his father spent a month in April and May 1905 on a shakedown cruise through the Ten Thousand Islands and on down the coast past Cape Sable to Florida Bay. It was on that initial cruise that they first met Seminole Indians at Storter’s store in Everglades City. From late May into June, they traveled north to Pine Island Sound and Charlotte Harbor and then returned to New York.

They were back again in January 1906 and spent the first five months of the year largely aboard the Irene sailing the coast from Marco to Cape Sable with many stops in between in the Ten Thousand Islands.

In June and perhaps early July of that year, the Dimocks had the Irene retrofitted to better serve their needs. A larger tank for fresh water was added, along with a darkroom for Julian. To accommodate the darkroom, the cabin was enlarged by removing the Irene’s aft mast. By late July, the Irene was ready for a trip down into the Ten Thousand Islands. Initially the plan was for the Dimocks, a local guide (Harrison), and two of the Irene “boys” to download a canoe, skiff, and the small motorboat from the Irene near the mouth of Rocky Creek in the Ten Thousand Islands north of Rodgers River. Then the motorboat was to tow the skiff and canoe up Rocky Creek until they reached a small seasonal Seminole camp they knew of. There they would leave the motorboat (which would be taken back to the Irene by some of the men), and the others would then paddle and pole their way east across the Everglades to Miami, photographing the Seminole Indians they met along the way.

As recounted in Hidden Seminoles, the plan went bad from the beginning. One of the Irene crew refused to go, and they replaced him with George Storter, owner of Storter’s store at Everglades City. He apparently intended to guide them into Rocky Creek and return with the motorboat. When they could not find the Seminole camp, it was decided that the water in the Glades was deep enough to continue on east with the motorboat towing the other two craft. Several days later, they could see smoke from Miami. What they did not see, though, were any Seminole Indians. The Seminoles, unsure of the motives of the five white people, simply hid.

After spending a short time in Miami, the Dimocks and their companions boarded their craft and traveled southward from Miami, through the Upper Keys, then up the Gulf coast to Everglades City and on to Marco Island. The entire journey took less than two weeks.

In September, in search of more adventures and land and seascapes to photograph, Julian and A. W. sailed the Irene north to Pine Island Sound and Charlotte Harbor. They did some fishing and also went up (and back down) the Myakka River.

In May 1907, the Dimocks returned to Florida and continued their explorations of the coast. Intent on again crossing the Everglades, in mid-August they returned to Storter’s store, where they hired Charley Tommy, a Seminole Indian, as a guide. Charley Tommy was well aware that it had been a dry year and that there was not enough water in some parts of the Everglades to float a canoe. Despite his admonitions, the two-canoe flotilla set out from Storter’s south into the Ten Thousand Islands before turning east into the Everglades. Just as Charley Tommy had predicted, the expedition was forced to abort after several days when it became clear that the water was too shallow to allow them to reach Miami. Even so, with Charley Tommy as guide, the Dimocks were able to gain entry into several Seminole camps and take photographs.

Unable to move east, they instead went north to Brown’s Boat Landing, a store near the boundary of the Big Cypress Swamp and the Everglades (about 35 miles southeast of present-day Immokalee). There Julian took more photographs of Seminole Indians. Bidding adieu to Charley Tommy and a man from Everglades City who had accompanied them, the Dimocks rented oxen and a cart from William Brown, owner and operator of Boat Landing, and, guided by Brown’s adult son Frank, loaded up their two canoes and equipment and traveled overland to the Caloosahatchee River several days to the north. Once there, they took leave of Frank Brown and the oxen, put their canoes in the river, and paddled back to Marco Island.

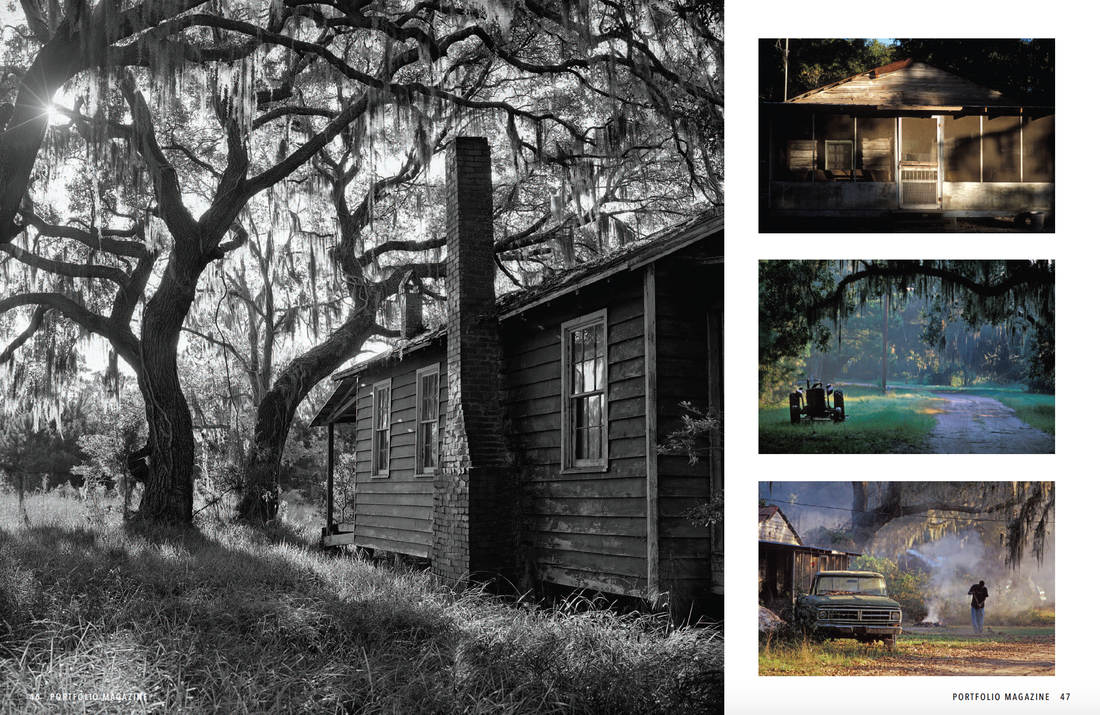

Early June 1908 saw the Dimocks back at Marco Island, again engaged in fishing and photography expeditions up and down the coast aboard the Irene. For the next three months, they traveled from Boca Grande down through the Ten Thousand Islands and back to Marco. At that point, they had spent a total of more than twenty-five months in southwest Florida.

The Dimocks did not return to Florida again until February 1910, and then they did not travel to Marco Island. Instead, a month was spent photographing truck farms and the citrus industry in north central and east Florida, around McIntosh, Lake Weir, Ocala, Sanford, and Cocoa (it is not certain that A. W. was with Julian). During the month, Julian traveled south from Cocoa to Fort Lauderdale and perhaps farther south before turning back north into central Florida. Using photographs of the farms and groves that he had visited, Julian wrote four articles for Country Life in America that appeared between November 1910 and February 1911. Some of the published photographs were colorized.

Later that year, Julian was persuaded by the anthropologist Alanson Skinner to accompany him as photographer on an American Museum of Natural History expedition to southern Florida to make collections of Seminole Indian items for the museum. That expedition resulted in Julian’s accumulating a collection of photographs, some showing Seminole people wearing or using clothing and other items that Skinner collected. Today, both the photographs and the objects, all well documented, are curated at the American Museum of Natural History, where some of the objects are on display in the Hall of North American Indians.

A .W. (whose first wife had died in 1901 and who remarried in 1909) and Julian would return to southwest Florida in mid-August 1913 with a small entourage that may have included their spouses. A. W., apparently wanting to impress some of his fellow members of the Camp Fire Club with the fishing amenities southwest Florida offered, invited William E. Coffin (president of the New York–based Camp Fire Club of which both Dimocks were members) and Gifford Pinchot (first chief of the United States Forest Service and governor of Pennsylvania in the 1920s and again in the 1930s and also a club member) along on the trip. Also with the Dimocks was Gilbert C. Demorest, a teenager whose father, William C., was a magazine publisher in New York and a club member.

The Dimocks and their guests took the train to Fort Myers, where a large houseboat—the Kennesaw—was rented to transport the group up and down the coast for a month. Julian again took photographs, the last he would take in Florida, and this time he also brought along a movie camera (though the whereabouts of any movies he made are not known). Five of the photographs he took of the men fishing were featured in an article in the New York Times on Sunday, February 1, 1914 (“Tarpon Fishing in Florida Waters Told in Pictures”).

By 1913, the frontier had caught up to Fort Myers. Since 1900, its population had more than doubled to around 2,900 people, and Lee County held about 6,600 residents. The Ten Thousand Islands, however, remained largely unpopulated. Across the interior of south Florida, the Seminole Indians continued to live in a number of small settlements. Through their growing interactions with the outside world, the Seminoles were laying the groundwork for the relative prosperity they would earn later in the twentieth century.

Julian Dimock’s photographs provide a valuable record of people and places that enables us to better understand and value our collective past and to appreciate southwest Florida’s natural history.

How This Project Came to Be

Prior to 1978, Julian’s glass-plate negatives were kept by the American Museum of Natural History’s General Service Department. In that year, they were transferred to the museum’s Research Library, where Nina Root, director, “discovered” them. Over the years, as time permitted, she became familiar with the thousands of images, and in August 1996 she published “Legacy of a Reluctant ‘Camera Man’ ” in Natural History magazine, a project that led to the book Camera Man’s Journey: Julian Dimock’s South (2002), edited by her and Thomas L. Johnson.

In 2007, Root invited Milanich to join her in research on Julian’s images from Florida, a collaboration that resulted in the book Hidden Seminoles: Julian Dimock’s Historic Florida Photographs (2011) and this volume.